Regenerative Frankincense

- Blair Butterfield

- May 2, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: May 7, 2022

plantLust utilizes the essential oil and resin known as frankincense. It is an ancient aromatic, a symbol of mysticism and of spiritual presence, and has been used as a plant ally for centuries. However, a lot of frankincense

in products or the essential oil market today supports harmful land practices and labor exploitation. We work with Stephen Johnson of FairSource Botanicals, who is on the ground in the unique and arid regions of the planet where these ancient trees grow, trying to create a regenerative, ethical, and transparent supply chain. I've spent a lot of time talking to Johnson; in fact, it has almost been three years that we have been working together and talking about frankincense, ethical commerce, and stewardship. Our conversations are deep and educational, and I think we always leave each other inspired to continue the work that we are both so passionate about.

In this blog post, I break down some of the conversations Stephen and I have had and share an insight into the current state of frankincense production. Also, please visit the FairSource Botanicals website for more information and to read about different types of Boswellia trees.

What is Frankincense?

Frankincense is the resin produced and exuded by trees in the genus Boswellia. There are currently 24 known species of Boswellia that produce frankincense resin, but there are only a few varieties commonly used to make essential oils. The resin is produced as a part of the tree's immune system. So when a tree is cut or nibbled by an insect, the tree exudes the resin to protect itself. It is full of chemical constituents with many beneficial properties. Some of these properties are maintained during essential oil production, making frankincense a potent and valuable botanical. Some even call it the King of essential oils.

Bees collecting resin of Boswellia sacra, photo courtesy FairSource Botanicals

Historically frankincense is one of the oldest aromatics. It has been used as medicine, perfume, and incense for thousands of years, with records dating as early as 3,000 B.C.E. from Mesopotamia. The resin has been found in ancient Egyptian tombs and utilized in Ayurvedic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, and in the works of ancient doctors such as the Islamic physician Ibn Sina (Avicenna). Through extensive lab analysis and GC/MS reports, we now know that frankincense resin has hundreds of chemical components, some being antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, sedative, antiarthritic, antirheumatic, calmative, and so much more.

Why do we need to regenerate frankincense?

According to Johnson, frankincense faces many challenges; indeed, it is one of the most complicated to source essential oils. The isolation and inaccessibility of the trees and the regions in which they grow have long cloaked the supply chains in mystery, making it easier for companies who source frankincense to use intermediaries rather than go direct to the source. Often a company that uses frankincense can not tell you where it comes from nor the species.

Johnson explains that the problem is the veil of secrecy that has remained in place as the demand for frankincense has skyrocketed. With more and more money flowing into the supply chain, this should be an opportunity to improve the lives of harvesters and their communities and confer greater value and protection on the trees. Instead, we’ve seen news stories repeatedly warning of challenges such as overharvesting, exploitation, abuse of communities and women, ongoing poverty, and unfair conditions, even as many companies have claimed they are sustainable and work directly with harvesters.

As Johnson sees it, the problem boils down to the simple fact that there can be no accountability without transparency. If companies can't see into the supply chain, know precisely how and where their frankincense is produced, they can't know if it's ethical. All too often, frankincense suppliers claim to "work directly with the harvesters" but then turn around and use a series of middlemen and intermediaries who siphon off most of the value of the resin. Through his on-the-ground working relationships, Johnson sees firsthand that the harvesters themselves and their communities remain deeply impoverished as they're offered rock-bottom prices and empty promises of community investment. As droughts are made more frequent by climate change, devastating the only other primary source of income in the region, livestock, harvesters are forced to tap the trees intensively with few rest periods to recover.

Boswellia sacra, photo courtesy FairSource Botanicals

Insight into Harvesting

Johnson has observed that while there have been some cultivation and plantation efforts, most frankincense is still wild-harvested. The land where the trees grow is usually privately owned by families or individuals. In Somaliland, for instance, where B. carteri is produced, harvesting areas are owned by families and passed down from father to son, which often preserves traditional harvesting practices that look at the trees with a long-term view of sustaining rather than a short term seasonal gain. When these generational practices are lost, it opens the way for seasonal harvesters to exploit these ancient trees, often to death.

On the other hand, B. neglecta trees in Kenya grow on communal land, where no one owns the land, and anyone who wants to collect resin can do so. This tree is unique as it does not require tapping. The trees naturally exude resin and are simply collected by hand, making it one of the most sustainable resin-producing Boswellia trees.

Harvesting Boswellia Neglecta, photo courtesy FairSource Botanicals

The actual act of harvesting resin involves cutting the tree's bark, similar to tapping for maple syrup, birch sap, copaiba, or sangre de grado. It is done during the dry season, and an average tree produces about half a kilo of resin per year. A harvester uses a knife called a mingaf, to shave a small patch of bark off the tree, exposing the resin canals and initiating the resin to ooze to the surface. In about two weeks, the harvester returns, scrapes the resin off the wound, then makes a deeper and wider cut to re-open the resin canals and allow more resin emerge. Johnson says that the number of cuts that can be made on a single tree depends on its size and health. The process is often intuitive to the harvester, who can gauge the tree's health. Once tapped, the trees should be left to rest and regenerate, which usually has a rhythm of 2-3 years of tapping and with one year of rest.

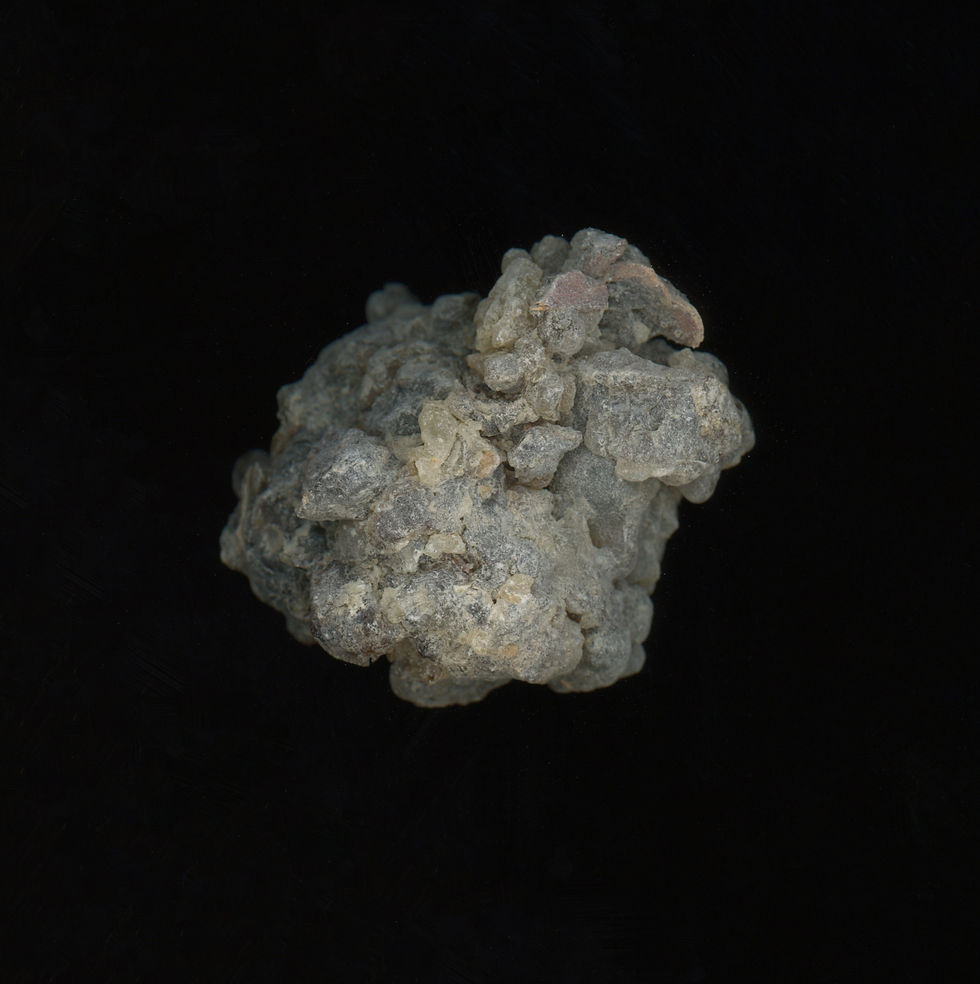

Boswellia sacra from Oman

plantLust uses the essential oil of boswellia sacra, which has a warm and sweet resinous scent that almost hints at pine sap. The tree grows in the Dhofar Mountains of southern Oman, and the fields there are privately owned by Dhofari tribes. According to FairSource Botanicals, these tribes have traditionally harvested the resin, but today the harvesting is almost all done on contract by Somali harvesters. The trees experienced high harvesting levels in the past, and concerns were raised about grazing camels. However, today, large areas appear to be untapped and regenerating well.

You can experience this oil in many of the products we offer, including our Frankincense Body Butter and Frankincense & Myrrh Bath Drops.

The Takeaway

plantLust was founded on the belief that what is done to the land is done to ourselves. Every resource we take from this planet can either nourish or deplete us. As consumers, we must make choices that help restore our planet and share prosperity, which means looking for ingredient transparency and educating ourselves on the issues surrounding a product's production. To us, FairSource Botanicals is paving a way to demonstrate how commerce can be sacred and reverent to the planet, its resources, its people, and our collective health.

To learn more about frankincense, visit some of our friend's project links below:

Comments